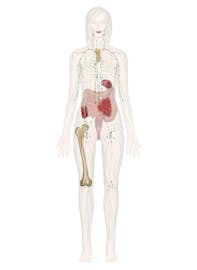

The Immune and Lymphatic Systems

Learn all about the vessels, nodes, nodules, and ducts of the lymphatic system. Learn about lymph itself, bone marrow, and the different types of immunity. 3D models help you explore the anatomy and physiology.

The immune and lymphatic systems are two closely related organ systems that share several organs and physiological functions. The immune system is our body's defense system against infectious pathogenic viruses, bacteria, and fungi as well as parasitic animals and protists. The immune system works to keep these harmful agents out of the body and attacks those that manage to enter.

The lymphatic system is a system of capillaries, vessels, nodes and other organs that transport a fluid called lymph from the tissues as it returns to the bloodstream. The lymphatic tissue of these organs filters and cleans the lymph of any debris, abnormal cells, or pathogens. The lymphatic system also transports fatty acids from the intestines to the circulatory system.

Immune and Lymphatic System Anatomy

Red Bone Marrow and Leukocytes

Red bone marrow is a highly vascular tissue found in the spaces between trabeculae of spongy bone. It is mostly found in the ends of long bones and in the flat bones of the body. Red bone marrow is a hematopoietic tissue containing many stem cells that produce blood cells. All of the leukocytes, or white blood cells, of the immune system are produced by red bone marrow. Leukocytes can be further broken down into 2 groups based upon the type of stem cells that produces them: myeloid stem cells and lymphoid stem cells.

Myeloid Stem Cells

Myeloid stem cells produce monocytes and the granular leukocytes---eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils.

Monocytes are agranular leukocytes that can form 2 types of cells: macrophages and dendritic cells.

- Macrophages. Monocytes respond slowly to infection and once present at the site of infection, develop into macrophages. Macrophages are phagocytes able to consume pathogens, destroyed cells, and debris by phagocytosis. As such, they have a role in both preventing infection as well as cleaning up the aftermath of an infection.

- Dendritic cells. Monocytes also develop into dendritic cells in healthy tissues of the skin and mucous membranes. Dendritic cells are responsible for the detection of pathogenic antigens which are used to activate T cells and B cells.

Granular Leukocytes include the following:

- Eosinophils. Eosinophils are granular leukocytes that reduce allergic inflammation and help the body fight off parasites.

- Basophils. Basophils are granular leukocytes that trigger inflammation by releasing the chemicals heparin and histamine. Basophils are active in producing inflammation during allergic reactions and parasitic infections.

- Neutrophils. Neutrophils are granular leukocytes that act as the first responders to the site of an infection. Neutrophils use chemotaxis to detect chemicals produced by infectious agents and quickly move to the site of infection. Once there, neutrophils ingest the pathogens via phagocytosis and release chemicals to trap and kill the pathogens.

Lymphoid Stem Cells

Lymphoid stem cells produce T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes.

- T lymphocytes. T lymphocytes, also commonly known as T cells, are cells involved in fighting specific pathogens in the body. T cells may act as helpers of other immune cells or attack pathogens directly. After an infection, memory T cells persist in the body to provide a faster reaction to subsequent infection by pathogens expressing the same antigen.

- B lymphocytes. B lymphocytes, also commonly known as B cells, are also cells involved in fighting specific pathogens in the body. Once B cells have been activated by contact with a pathogen, they form plasma cells that produce antibodies. Antibodies then neutralize the pathogens until other immune cells can destroy them. After an infection, memory B cells persist in the body to quickly produce antibodies to subsequent infection by pathogens expressing the same antigen.

- Natural killer cells. Natural killer cells, also known as NK cells, are lymphocytes that are able to respond to a wide range of pathogens and cancerous cells. NK cells travel within the blood and are found in the lymph nodes, spleen, and red bone marrow where they fight most types of infection.

Lymph Capillaries

As blood passes through the tissues of the body, it enters thin-walled capillaries to facilitate diffusion of nutrients, gases, and wastes. Blood plasma also diffuses through the thin capillary walls and penetrates into the spaces between the cells of the tissues. Some of this plasma diffuses back into the blood of the capillaries, but a considerable portion becomes embedded in the tissues as interstitial fluid. To prevent the accumulation of excess fluids, small dead-end vessels called lymphatic capillaries extend into the tissues to absorb fluids and return them to circulation.

Lymph

The interstitial fluid picked up by lymphatic capillaries is known as lymph. Lymph very closely resembles the plasma found in the veins: it is a mixture of about 90% water and 10% solutes such as proteins, cellular waste products, dissolved gases, and hormones. Lymph may also contain bacterial cells that are picked up from diseased tissues and the white blood cells that fight these pathogens. In late-stage cancer patients, lymph often contains cancerous cells that have metastasized from tumors and may form new tumors within the lymphatic system. A special type of lymph, known as chyle, is produced in the digestive system as lymph absorbs triglycerides from the intestinal villi. Due to the presence of triglycerides, chyle has a milky white coloration to it.

Lymphatic Vessels

Lymphatic capillaries merge together into larger lymphatic vessels to carry lymph through the body. The structure of lymphatic vessels closely resembles that of veins: they both have thin walls and many check valves due to their shared function of carrying fluids under low pressure. Lymph is transported through lymphatic vessels by the skeletal muscle pump---contractions of skeletal muscles constrict the vessels to push the fluid forward. Check valves prevent the fluid from flowing back toward the lymphatic capillaries.

Lymph Nodes

Lymph nodes are small, kidney-shaped organs of the lymphatic system. There are several hundred lymph nodes found mostly throughout the thorax and abdomen of the body with the highest concentrations in the axillary (armpit) and inguinal (groin) regions. The outside of each lymph node is made of a dense fibrous connective tissue capsule. Inside the capsule, the lymph node is filled with reticular tissue containing many lymphocytes and macrophages. The lymph nodes function as filters of lymph that enters from several afferent lymph vessels. The reticular fibers of the lymph node act as a net to catch any debris or cells that are present in the lymph. Macrophages and lymphocytes attack and kill any microbes caught in the reticular fibers. Efferent lymph vessels then carry the filtered lymph out of the lymph node and towards the lymphatic ducts.

Lymphatic Ducts

All of the lymphatic vessels of the body carry lymph toward the 2 lymphatic ducts: the thoracic duct and the right lymphatic ducts. These ducts serve to return lymph back to the venous blood supply so that it can be circulated as plasma.

- Thoracic duct. The thoracic duct connects the lymphatic vessels of the legs , abdomen, left arm, and the left side of the head, neck, and thorax to the left brachiocephalic vein.

- Right lymphatic duct. The right lymphatic duct connects the lymphatic vessels of the right arm and the right side of the head, neck, and thorax to the right brachiocephalic vein.

Lymphatic Nodules

Outside of the system of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes, there are masses of non-encapsulated lymphatic tissue known as lymphatic nodules. The lymphatic nodules are associated with the mucous membranes of the body, where they work to protect the body from pathogens entering the body through open body cavities.

- Tonsils. There are 5 tonsils in the body---2 lingual, 2 palatine, and 1 pharyngeal. The lingual tonsils are located at the posterior root of the tongue near the pharynx. The palatine tonsils are in the posterior region of the mouth near the pharynx. The pharyngeal pharynx, also known as the adenoid, is found in the nasopharynx at the posterior end of the nasal cavity. The tonsils contain many T and B cells to protect the body from inhaled or ingested substances. The tonsils often become inflamed in response to an infection.

- Peyer's patches. Peyer's patches are small masses of lymphatic tissue found in the ileum of the small intestine. Peyer's patches contain T and B cells that monitor the contents of the intestinal lumen for pathogens. Once the antigens of a pathogen are detected, the T and B cells spread and prepare the body to fight a possible infection.

- Spleen. The spleen is a flattened, oval-shaped organ located in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen lateral to the stomach. The spleen is made up of a dense fibrous connective tissue capsule filled with regions known as red and white pulp. Red pulp, which makes up most of the spleen's mass, is so named because it contains many sinuses that filter the blood. Red pulp contains reticular tissues whose fibers filter worn out or damaged red blood cells from the blood. Macrophages in the red pulp digest and recycle the hemoglobin of the captured red blood cells. The red pulp also stores many platelets to be released in response to blood loss. White pulp is found within the red pulp surrounding the arterioles of the spleen. It is made of lymphatic tissue and contains many T cells, B cells, and macrophages to fight off infections.

- Thymus. The thymus is a small, triangular organ found just posterior to the sternum and anterior to the heart. The thymus is mostly made of glandular epithelium and hematopoietic connective tissues. The thymus produces and trains T cells during fetal development and childhood. T cells formed in the thymus and red bone marrow mature, develop, and reproduce in the thymus throughout childhood. The vast majority of T cells do not survive their training in the thymus and are destroyed by macrophages. The surviving T cells spread throughout the body to the other lymphatic tissues to fight infections. By the time a person reaches puberty, the immune system is mature and the role of the thymus is diminished. After puberty, the inactive thymus is slowly replaced by adipose tissue.

Immune and Lymphatic System Physiology

Lymph Circulation

One of the primary functions of the lymphatic system is the movement of interstitial fluid from the tissues to the circulatory system. Like the veins of the circulatory system, lymphatic capillaries and vessels move lymph with very little pressure to help with circulation. To help move lymph towards the lymphatic ducts, there is a series of many one-way check valves found throughout the lymphatic vessels. These check valves allow lymph to move toward the lymphatic ducts and close when lymph attempts to flow away from the ducts. In the limbs, skeletal muscle contraction squeezes the walls of lymphatic vessels to push lymph through the valves and towards the thorax. In the trunk, the diaphragm pushes down into the abdomen during inhalation. This increased abdominal pressure pushes lymph into the less pressurized thorax. The pressure gradient reverses during exhalation, but the check valves prevent lymph from being pushed backwards.

Transport of Fatty Acids

Another major function of the lymphatic system is the transportation of fatty acids from the digestive system. The digestive system breaks large macromolecules of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids into smaller nutrients that can be absorbed through the villi of the intestinal wall. Most of these nutrients are absorbed directly into the bloodstream, but most fatty acids, the building blocks of fats, are absorbed through the lymphatic system.

In the villi of the small intestine are lymphatic capillaries called lacteals. Lacteals are able to absorb fatty acids from the intestinal epithelium and transport them along with lymph. The fatty acids turn the lymph into a white, milky substance called chyle. Chyle is transported through lymphatic vessels to the thoracic duct where it enters the bloodstream and travels to the liver to be metabolized.

Types of Immunity

The body employs many different types of immunity to protect itself from infection from a seemingly endless supply of pathogens. These defenses may be external and prevent pathogens from entering the body. Conversely, internal defenses fight pathogens that have already entered the body. Among the internal defenses, some are specific to only one pathogen or may be innate and defend against many pathogens. Some of these specific defenses can be acquired to preemptively prevent an infection before a pathogen enters the body.

The body has many innate ways to defend itself against a broad spectrum of pathogens. These defenses may be external or internal defenses.

External defenses include the following:

- The coverings and linings of the body constantly prevent infections before they begin by barring pathogens from entering the body. Epidermal cells are constantly growing, dying, and shedding to provide a renewed physical barrier to pathogens.

- Secretions like sebum, cerumen, mucus, tears, and saliva are used to trap, move, and sometimes even kill bacteria that settle on or in the body. Stomach acid acts as a chemical barrier to kill microbes found on food entering the body. Urine and acidic vaginal secretions also help to kill and remove pathogens that attempt to enter the body.

- The flora of naturally occurring beneficial bacteria that live on and in our bodies provide a layer of protection from harmful microbes that would seek to colonize our bodies for themselves.

Internal defenses include fever, inflammation, natural killer cells, and phagocytes. Let's explore internal defenses in greater detail.

Fever

In response to an infection, the body may start a fever by raising its internal temperature out of its normal homeostatic range. Fevers help to speed up the body's response system to an infection while at the same time slowing the reproduction of the pathogen.

Inflammation

The body may also start an inflammation in a region of the body to stop the spread of the infection. Inflammations are the result of a localized vasodilation that allows extra blood to flow into the infected region. The extra blood flow speeds the arrival of leukocytes to fight the infection. The enlarged blood vessel allows fluid and cells to leak out of the blood vessel to cause swelling and the movement of leukocytes into the tissue to fight the infection.

Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer (NK) cells are special lymphocytes that are able to recognize and kill virus-infected cells and tumor cells. NK cells check the surface markers on the surface of the body's cells, looking for cells that are lacking the correct number of markers due to disease. The NK cells then kill these cells before they can spread infection or cancer.

Phagocytes

The term phagocyte means "eating cell" and refers to a group of cell types including neutrophils and macrophages. A phagocyte engulfs pathogens with its cell membrane before using digestive enzymes to kill and dissolve the cell into its chemical parts. Phagocytes are able to recognize and consume many different types of cells, including dead or damaged body cells.

Cell-mediated Specific Immunity

When a pathogen infects the body, it often encounters macrophages and dendritic cells of the innate immune system. These cells can become antigen-presenting cells (APCs) by consuming and processing pathogenic antigens. The APCs travel into the lymphatic system carrying these antigens to be presented to the T cells and B cells of the specific immune system.

Inactive T cells are found in lymphatic tissue awaiting infection by a pathogen. Certain T cells have antigen receptors that recognize the pathogen but do not reproduce until they are triggered by an APC. The activated T cell begins reproducing very quickly to form an army of active T cells that spread through the body and fight the pathogen. Cytotoxic T cells directly attach to and kill pathogens and virus-infected cells using powerful toxins. Helper T cells assist in the immune response by stimulating the response of B cells and macrophages.

After an infection has been fought off, memory T cells remain in the lymphatic tissue waiting for a new infection by cells presenting the same antigen. The response by memory T cells to the antigen is much faster than that of the inactive T cells that fought the first infection. The increase in T cell reaction speed leads to immunity---the reintroduction of the same pathogen is fought off so quickly that there are few or no symptoms. This immunity may last for years or even an entire lifetime.

Antibody-mediated Specific Immunity

During an infection, the APCs that travel to the lymphatic system to stimulate T cells also stimulate B cells. B cells are lymphocytes that are found in lymphatic tissues of the body that produce antibodies to fight pathogens (instead of traveling through the body themselves). Once a B cell has been contacted by an APC, it processes the antigen to produce an MHC-antigen complex. Helper T cells present in the lymphatic system bind to the MHC-antigen complex to stimulate the B cell to become active. The active B cell begins to reproduce and produce 2 types of cells: plasma cells and memory B cells.

- Plasma cells become antibody factories producing thousands of antibodies.

- Memory B cells reside in the lymphatic system where they help to provide immunity by preparing for later infection by the same antigen-presenting pathogen.

Antibodies are proteins that are specific to and bind to a particular antigen on a cell or virus. Once antibodies have latched on to a cell or virus, they make it harder for their target to move, reproduce, and infect cells. Antibodies also make it easier and more appealing for phagocytes to consume the pathogen.

Acquired Immunity

Under most circumstances, immunity is developed throughout a lifetime by the accumulation of memory T and B cells after an infection. There are a few ways that immunity can be acquired without exposure to a pathogen. Immunization is the process of introducing antigens from a virus or bacterium to the body so that memory T and B cells are produced to prevent an actual infection. Most immunizations involve the injection of bacteria or viruses that have been inactivated or weakened. Newborn infants can also acquire some temporary immunity from infection thanks to antibodies that are passed on from their mother. Some antibodies are able to cross the placenta from the mother's blood and enter the infant's bloodstream. Other antibodies are passed through breast milk to protect the infant.