Macronutrients

Learn all about the nutritional importance of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, as well as good dietary sources of each.

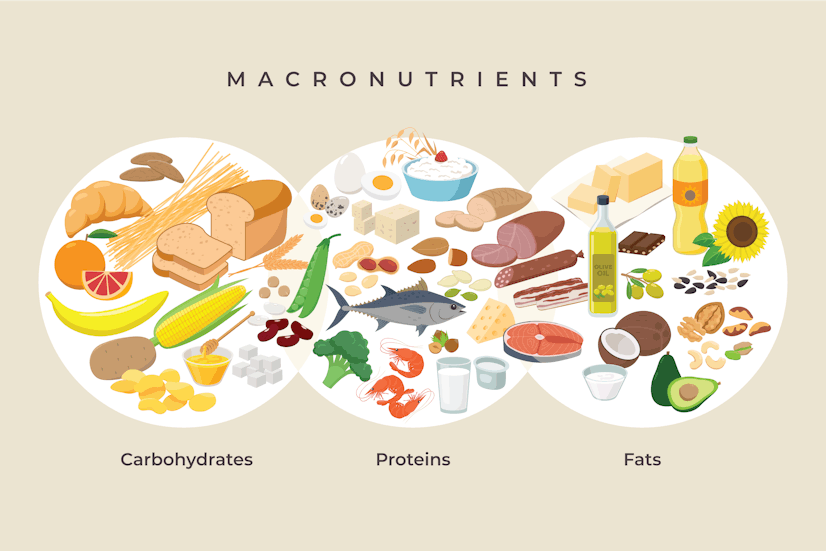

Carbohydrates, fats and proteins are macronutrients. We require them in relatively large amounts for normal function and good health. These are also energy-yielding nutrients, meaning these nutrients provide calories.

Jump to:

Carbohydrates

Every few years, carbohydrates are vilified as public enemy number one and are accused of being the root of obesity, diabetes, heart disease and more. Carb-bashers shun yogurt and fruit and fill up on bun-less cheeseburgers. Instead of beans, they eat bacon. They dine on the tops of pizza and toss the crusts into the trash. They so vehemently avoid carbs and spout off a list of their evils that they may have you fearing your food. Rest assured, you can and should eat carbohydrates. In fact, much of the world relies on carbohydrates as their major source of energy. Rice, for instance, is a staple in Southeast Asia. The carbohydrate-rich potato was so important to the people of Ireland that when the blight devastated the potato crop in the mid 1800s, much of the population was wiped out.

What are Carbohydrates?

The basic structure of carbohydrates is a sugar molecule, and they are classified by how many sugar molecules they contain.

Simple carbohydrates, usually referred to as sugars, are naturally present in fruit, milk and other unprocessed foods. Plant carbohydrates can be refined into table sugar and syrups, which are then added to foods such as sodas, desserts, sweetened yogurts and more. Simple carbohydrates may be single sugar molecules called monosaccharides or two monosaccharides joined together called disaccharides. Glucose, a monosaccharide, is the most abundant sugar molecule and is the preferred energy source for the brain. It is a part of all disaccharides and the only component of polysaccharides. Fructose is another common monosaccharide. Two common disaccharides in food are sucrose, common table sugar, and lactose, the source of frequent gas and bloating that some experience from drinking milk. Complex carbohydrates are any that contain more than two sugar molecules. Short chains are called oligosaccharides. Chains of more than ten monosaccharides linked together are called polysaccharides. They may be hundreds and even thousands of glucose molecules long. The way glucose molecules link together makes them digestible (starch) or non-digestible (fiber). Polysaccharides include the following.

- Starch is a series of long chains of bound glucose molecules. It's the storage form of glucose for grains, tubers and legumes and is used during the plant's growth and reproduction.

- Fiber is also long chains of glucose molecules, but they are bound in a way we cannot digest.

- Glycogen is the storage form of glucose in humans and other animals. It's not a dietary source of carbohydrate because it is quickly broken down after an animal is slaughtered.

Carbohydrates in the Body

Whether they're from a doughy bagel, a sugary cola or a fiber-rich apple, carbohydrates' primary job is to provide your body with energy. From each of these sources and others, carbohydrates provide you with 4 kcals/gram.

- Carbs are fuel. Glucose is the primary fuel for most of your cells and is the preferred energy for the brain and nervous system, the red blood cells and the placenta and fetus. Once glucose enters the cell, a series of metabolic reactions convert it to carbon dioxide, water and ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the energy currency of the cell. If you have more available glucose than your body needs for energy, you will store glucose as glycogen (glycogenesis) in your liver and skeletal muscle. When your blood glucose drops, as it does when you're sleeping or fasting, the liver will break down glycogen (glycogenolysis) and release glucose into your blood. Muscle glycogen fuels your activity. The body can store just a limited amount of glucose, so when the glycogen stores are full, extra glucose is stored as fat and can be used as energy when needed.

- Carbs spare protein. If you go without eating for an extended period or simply consume too little carbohydrate, your glycogen stores will quickly deplete. Your body will grab protein from your diet (if available), skeletal muscles and organs and convert its amino acids into glucose (gluconeogenesis) for energy and to maintain normal blood glucose levels. This can cause muscle loss, problems with immunity and other functions of proteins in the body. That's how critical it is to maintain normal blood glucose levels to feed parts of your body and your brain.

- Carbs prevent ketosis. Even when fat is used for fuel, the cells need a bit of carbohydrate to completely break it down. Otherwise, the liver produces ketone bodies, which can eventually build up to unsafe levels in the blood causing a condition called ketosis. If you ever noticed the smell of acetone or nail polish remover on the breath of a low-carb dieter, you have smelled the effects of ketosis. Ketosis can also cause the blood to become too acidic and the body to become dehydrated.

Carbohydrates in the Diet

Carbohydrates, protein and fats are macronutrients, meaning the body requires them in relatively large amounts for normal functioning. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for carbohydrates for children and adults is 130 grams and is based on the average minimum amount of glucose used by the brain.1 The Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) for carbohydrates is 45-65%. If, for instance, you ate 1600 kcals per day, the acceptable carbohydrate intake ranges from 180 grams to 260 grams.

Most American adults consume about half of their calories as carbohydrates. This falls within the AMDR, but unfortunately most Americans do not choose their carbohydrate-containing foods wisely. Many people label complex carbs as good and sugars as bad, but the carbohydrate story is much more complex than that. Both types yield glucose through digestion or metabolism; both work to maintain your blood glucose; both provide the same number of calories; and both protect your body from protein breakdown and ketosis. The nutrient-density of our food choices is far more critical. For example, fresh cherries provide ample sugars, and saltine crackers provide just complex carbs. Few would argue that highly processed crackers are more nutritious than fresh cherries.

Added Sugars

Americans eat only 42% of the recommended amount of fruit and 59% of the recommended vegetable amount. We eat only 15% of the recommended servings of whole grains, but 200% of the recommended servings of refined grains.2 Americans over-consume added-sugars, which make up 16% of the total calories in the American diet. Nearly 60% of added sugars come from soda, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and grain-based desserts like cakes, cookies and brownies.3 The problem with added sugars is that they do not come packaged with an abundance of nutrients like a piece of fruit and a glass of milk do. For this reason, many people call them empty calories.

Glycemic Index

Sometimes people look to the glycemic index (GI) to evaluate the healthfulness of carbohydrate-rich foods, but this too oversimplifies good nutrition. The GI ranks carbohydrate-containing foods from 0 to 100. This score indicates the increase in blood glucose from a single food containing 50 grams of carbohydrate compared to 50 grams of pure glucose, which has a GI score of 100. Foods that are slowly digested and absorbed - like apples and some bran cereals - trickle glucose into your bloodstream and have low GI scores. High GI foods like white bread and cornflakes are quickly digested and absorbed, flooding the blood with glucose. Research regarding the GI is mixed; some studies suggest that diets based on low GI foods are linked to lower risks of diabetes, obesity and heart disease, but other studies fail to show such a link.

Many factors influence a food's GI score, including:

- The degree of ripeness of a piece of fruit (the riper the fruit, the higher the score)

- The amount and type of processing a food has undergone

- Whether the food is eaten raw or cooked

- The presence of fat, vinegar or other acids

All of these factors complicate the usefulness of the GI. Additionally, many high-calorie, low-nutrient foods such as some candy bars and ice creams have desirable GI scores, while more nutritious foods like dates and baked potatoes have high scores. It's important to recognize that the healthfulness of a food depends largely on its nutrient density, not its type of carbohydrate or its GI score.

Proponents of low-carbohydrate diets are incensed by the RDA and AMDR for carbohydrates. "Nutrition experts are trying to kill us," they argue and claim that carbohydrates have made us overweight. However, research supports that diets of a wide range of macronutrient proportions facilitate a healthy weight, allow weight loss and prevent weight regain. The critical factor is reducing the calorie content of the diet long-term.4 5

Fiber Needs

If we shunned all carbohydrates or if we severely restricted them, we would not be able to meet our fiber needs or get ample phytochemicals, naturally occurring compounds that protect the plant from infection and us from chronic disease. The hues, aromas and flavors of the plant suggest that it contains phytochemicals. Scientists have learned of thousands of them with names like lycopene, lutein and indole-3-carbinol. Among other things, phytochemicals appear to stimulate the immune system, slow the rate at which cancer cells grow, and prevent damage to DNA.

All naturally fiber-rich foods are also rich in carbohydrates. The recommended intake for fiber is 38 grams per day for men and 25 grams per day for women. The usual fiber intake among Americans, however, is woefully lacking at only 15 grams daily. Perhaps best known for its role in keeping the bowels regular, dietary fiber has more to brag about. Individuals with high fiber intakes appear to have lower risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes and obesity.6 Fiber-rich foods are protective against colorectal cancer7, and increasing fiber intakes improves gastroesophageal reflux disease and hemorrhoids.6 Some fibers also lower blood cholesterol and glucose levels. Additionally, fibers are food for the normal (healthy) bacteria that reside in your gut and provide nutrients and other health benefits. To boost your fiber intake, eat fruits, vegetables, whole grains and beans frequently.

Fiber Content of Selected Foods

- Beans (navy, pinto, black, lima etc), 1/2 cup: 6.2 - 9.6 g

- 100% Bran cereal, 1/3 cup: 9.1 g

- Pear, medium: 5.5 g

- Whole-wheat English muffin, 1: 4.4 g

- Raspberries, 1/2 cup: 4.0 g

- Sweet potato with skin, medium: 3.8 g

- Apple with skin, 1 medium: 3.6 g

- Orange, medium: 3.1 g

- Potato with skin, 1 medium: 3.0 g

- Broccoli, cooked, 1/2 cup: 2.6 - 2.8 g

Source: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2011 (Appendix 13)

Carbohydrates are critical sources of energy for several body systems. Nourish your body and help shield yourself from chronic disease by getting most of your carbohydrates from fruits, whole grains, legumes, milk and yogurt. Limit added sugars and heavily processed grains.

Proteins

What's for dinner? In the U.S, this question is usually answered with some type of meat like pot roast, chicken, salmon or meatloaf. Meat, because it's rich in protein, is usually central to the meal, and vegetables and grains are frequently the afterthought. This may give the impression that a meal isn't complete without meat and that we need lots of meat or protein for good health. The truth is, most Americans eat much more protein than their bodies require. And even if you choose to eat no meat at all, you can still meet your protein needs.

Proteins in the Body

Like carbohydrates and lipids, proteins are one of the macronutrients. Though protein provides your body with 4 kcals per gram, giving you energy is not its primary role. Rather, it's got way too many other things going on. In fact, your body contains thousands of different proteins, each with a unique function. Their building blocks are nitrogen-containing molecules called amino acids. If your cells have all 20 amino acids available in ample amounts, you can make an infinite number of proteins. Nine of those 20 amino acids are essential, meaning you must get them in the diet.

- Some proteins are enzymes. Enzymes speed up chemical actions such as the digestion of carbohydrates or the synthesis of cholesterol by the liver. They increase the rate of chemical reactions so much that not having them because of a genetic defect can be catastrophic.

- Some proteins are hormones. Hormones are chemicals that are created in one part of the body and carry messages to another organ or part of the body. For example, both glucagon and insulin are hormones that are made in the pancreas and travel throughout the body to regulate blood glucose.

- Some proteins provide structure. The protein collagen gives structure to bones, teeth and skin. Hair and nails depend on keratin.

- Some proteins are antibodies. Without adequate protein, your immune system cannot properly defend you against bacteria, viruses and other invaders. Antibodies are the blood proteins that attack and neutralize these invaders.

- Proteins maintain fluid balance. Fluid is present in many compartments of your body. It is within the cells (intracellular fluid), in the blood (intravascular fluid) and between the cells (interstitial fluid). Fluids also flow between these spaces. It's the proteins and minerals that keep them in balance. Proteins are too large to pass freely across the membranes separating the compartments, but since proteins attract water, they act to maintain proper fluid balance. If your protein intake is too low to maintain normal blood protein levels, fluid will leak into the surrounding tissues and cause swelling called edema.

- Proteins transport nutrients and other compounds. Some proteins sit inside your cell membranes pumping compounds in and out of the cell. Others attach themselves to nutrients or other molecules to transport them to distant parts of the body. Hemoglobin, which carries oxygen, is one such protein.

- Proteins maintain acid-base balance. Blood that is too acidic or too alkaline will kill you. Fortunately, the body regulates its acid-base balance very tightly. One mechanism uses proteins as buffers. Proteins have negative charges that pick up positively charged hydrogen ions when conditions are too acidic. Hydrogen ions can then be released when the blood is too alkaline. To illustrate the dire consequences of an acid-base imbalance, think about what happens to proteins in an environment too acid or alkaline. They get denatured which changes their shape and renders them useless. Hemoglobin, for example, would not be able to carry oxygen throughout your body.

- Protein is a backup source of energy. With so many jobs, you can see why protein is not used as a primary source of energy. But rather than allowing your brain to go without glucose in times of starvation or low carbohydrate intake, the body sacrifices protein from your muscles and other tissues or takes it from the diet (if available) in order to make new glucose from amino acids in a process called gluconeogenesis.

Proteins in the Diet

Bodybuilders drink protein shakes for breakfast and after working out. Dieters with no time to stop for lunch grab protein bars. Are these strategies necessary for optimal strength building and weight loss? Probably not.

Proteins in the body are constantly broken down and resynthesized. Our bodies reuse most of the released amino acids, but a small portion is lost and must be replaced in the diet. The requirement for protein reflects this lost amount of amino acids plus any increased needs from growth or illness. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein for adults is 0.8 g/kg of body weight. Because of their rapid growth, infants have the highest RDA for protein at 1.5 g/kg of body weight. The RDA gradually decreases until adulthood. It increases again during pregnancy and lactation to a level of 1.1 g/kg. The RDA for an adult weighing 140 pounds (63.6 kg) is a mere 51 grams of protein, an amount many of us consume before mid-afternoon.

Physical Activity

The RDA remains the same regardless of physical activity level. There is some data, however, suggesting that both endurance and strength athletes have increased protein needs compared to inactive individuals. Endurance athletes may need as much as 1.4 g/kg, and strength athletes may require as much as 1.7 g/kg.8 A bodybuilder weighing 200 pounds (90.9 kg) may then need as much as 155 grams of protein.

Age

The Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) for protein for men and women age 19 and older is 10-35% of total calories. For children age 4 and over, it is 10-30%, and for younger children, the range is 5-20%. For an adult consuming 1600 kcals per day, the acceptable protein intake ranges from 40-140 grams per day, an amount easily met. Consider the 200-pound bodybuilder whose protein needs are approximately 155 grams per day. With energy needs approximately 4500 kcals per day, his protein needs are only 14% of his total calories --- well within the AMDR. With his energy needs so great, however, his diet will need careful planning. If he requires engineered foods such as bars and shakes, it will most likely be to meet his energy needs rather than his protein needs.

One population that needs special attention is the elderly. Though the RDA for older adults remains the same as for younger adults, some research suggests their needs may be 1.2 grams/kg body weight in order to prevent the common muscle loss and osteoporosis that come along with aging.9 Though this doesn't require the elderly to eat large servings of food, they frequently have poor appetites and dental problems that make chewing difficult. Helping them meet their nutritional needs may take a little creativity and perseverance.

Vegetarian Diets

People become vegetarian for a variety of reasons including religious beliefs, health concerns, and a concern for animals or for the environment. Oftentimes, "How can I get my protein?" is the first question asked when people discuss their choice for vegetarianism. Yes, in the typical American diet, most of our protein comes from animal foods. It is possible, however, to meet all of your protein needs while consuming a vegetarian diet. You can even eat adequate protein on a carefully planned vegan diet - a diet that excludes all animal products, including eggs and dairy.

When you think of protein, like most people, you probably think of beef, chicken, turkey, fish and dairy products. Beans and nuts might come to mind as well. Most foods contain at least a little protein, so by eating a diet with variety, vegetarians and vegans can eat all the protein they need without special supplements.

This list illustrates the amount of protein found in common foods that may be included in your diet.

Approximate Protein Content of Selected Foods

- Poultry, beef, fish, 4 ounce: 28g

- Broccoli, 1 cup cooked: 6g

- Milk, 8-fluid ounce: 8g

- Peanut butter, 2 Tbsp: 8g

- Kidney beans, 1 cup: 13g

- Whole-wheat bread, 1 slice: 4g

A complete protein includes all of the essential amino acids. Complete proteins include all animal proteins and soy. Incomplete proteins lack one or more essential amino acids. Beans, nuts, grains and vegetables are incomplete proteins. Previously, registered dietitians and physicians advised vegetarians to combine foods that contained incomplete proteins at the same meal to give the body all the necessary amino acids it needed at one time. Today we know this is unnecessary. Your body combines complementary or incomplete proteins that are eaten in the same day.10

If you eat a variety of foods, you will meet your protein needs. Recreational athletes rarely need protein supplements. Professional athletes should consult a registered dietitian (RD) who is also a Certified Specialist in Sports Dietetics (CSSD). If you are vegetarian or vegan, it's wise to see a registered dietitian for careful planning of your diet to meet not just your protein needs, but other nutrients as well.

Fats

It all started in the '80s. Doctors, nutritionists and public health officials told us to stop eating so much fat. Cut back on fat, they said, to lose weight and fend off heart disease among other ills. Americans listened, but that didn't improve our food choices. Rather, low-fat food labels seduced us, and we made pretzels and fat-free, sugar-rich desserts our grocery staples. Today we know to focus on the quality of the fat instead of simply the quantity.

Fats in the Body

Say NO to very low-fat diets. Why? Many people find them limiting, boring, tasteless and hard to stick to. And because fat tends to slow down digestion, many low-fat dieters fight hunger pangs all day or eat such an abundance of low-fat foods that their calorie intake is too great for weight loss.

Dietary fat has critical roles in the body. Each gram of fat, whether it's from a spoon of peanut butter or a stick of butter, provides 9 kcals. This caloric density is a lifesaver when food is scarce and is important for anyone unable to consume large amounts of food. The elderly, the sick and others with very poor appetites benefit from high-fat foods. Because their tiny tummies can't hold big volumes, small children too need fat to provide enough calories for growth.

- Fats are an energy reserve. Your body can store just small amounts of glucose as glycogen for energy, but you can put away unlimited amounts of energy as fat tissue. This is a problem in our world of excess calories, but was necessary in earlier times when food was scarce. You'll use this stored energy while you're sleeping, during periods of low energy intake and during physical activity.

- Fats provide essential fatty acids (EFA). Fatty acids differ chemically by the length of their carbon chains, the degree of saturation (how many hydrogen atoms are bound to carbon) and the location of carbon-carbon double bonds. These are critical differences that give each fatty acid unique functions. Our bodies are amazing machines capable of producing most of the needed fatty acids. There are two fatty acids that it cannot make at all, however. They are called LA (linoleic acid) and ALA (alpha linolenic acid). This makes LA and ALA "essential", meaning they must be obtained through the diet. In the body, fatty acids are important constituents of cell membranes, and they are converted to chemical regulators that affect inflammation, blood clotting, blood vessel dilation and more. Clinical deficiencies are rare. A deficiency of LA is usually seen in people with severe malabsorption problems. Its symptoms are poor growth in children, decreased immune function, and a dry, scaly rash. In the few cases of ALA deficiency that doctors and researchers are aware of, the symptoms were visual problems and nerve abnormalities.

- Fats carry fat-soluble nutrients. Dietary fats dissolve and transport fat-soluble nutrients, such as some vitamins and also disease-fighting phytochemicals like the carotenoids alpha- and beta-carotene and lycopene. To illustrate, researchers were able to detect only negligible amounts of absorbed carotenoids in the blood of individuals who had eaten a tossed salad with fat-free salad dressing. With reduced-fat dressing, the study participants absorbed some carotenoids, but with full-fat dressing, they absorbed even more.11

- Fats add to the texture and flavor of foods. You already know that fat makes food taste good. That's partly because fats dissolve flavorful, volatile chemicals. They also add a rich, creamy texture, giving food a satisfying mouthfeel. Imagine the texture of fat-free chocolate. Not good, probably. Finally, fats provide a tenderness and moistness to baked goods.

Fats in the Diet

Fats and oils (collectively known as lipids) contain mixtures of fatty acids. You may refer to olive oil as a monounsaturated fat. Many people do. Really, however, olive oil contains a combination of monounsaturated, saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, but it has more monounsaturated fatty acids than other types. Similarly, it is technically incorrect to call lard a saturated fat. It does contain mostly saturated fatty acids, but both monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids are present as well.

There is no Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) or Adequate Intake (AI) for total fat intake for any population other than infants. Depending on the age, the AI for infants is 30 or 31 grams of fat per day. The Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) is 20-35% for men and women age 19 years and older. For an adult consuming 1600 kcals then, the acceptable fat intake ranges from 35 to 62 grams daily. The AMDR for children is higher and varies by age, starting out at 30-40% for children ages 1 to 3 and gradually approaching the AMDR for adults. Experts discourage low-fat diets for infants, toddlers and young children because fat is energy-dense, making it appropriate for small, finicky appetites and to support growth and the developing central nervous system. The AIs for LA and ALA for adults range from 11-17 grams and 1.1 to 1.6 grams, respectively.

Saturated Fats

Because your body can make all the saturated fatty acids it needs, you do not need any in the diet. High intakes of most saturated fatty acids are linked to high levels of LDL (low-density lipoprotein), or bad, cholesterol and reduced insulin sensitivity.12 According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010, we should limit our intake of saturated fatty acids to 10% of our total calorie intake (18 grams for someone eating 1600 kcals daily) to reduce LDL cholesterol and our risk for heart disease. The American Heart Association favors a greater restriction to just 7% of total calories (12 grams for a 1600 kcal diet). If you tried to eat no saturated fatty acids, however, you would soon find that you had little to eat. Remember that fats are combinations of fatty acids, so even nuts and salmon (good sources of healthy fats) contain some saturated fatty acids.

What does bacon grease look like after the pan has cooled? Its firmness is a hint that bacon is high in saturated fat. Many saturated fats are solid at room temperature. Dairy fat and the tropical oils (coconut, palm and palm kernel) are also largely saturated. The greatest sources of saturated fat in the American diet are full-fat cheese, pizza and desserts.13

The benefit you experience from reducing your intake of saturated fats depends on many factors, including what you replace them with. Loading up on fat-free pretzels and gummy candies may be tempting, but is a misguided strategy because diets high in heavily refined carbohydrates typically increase triglycerides and lower the beneficial HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, both risk factors for heart disease. A better strategy is to replace the foods rich in unhealthy fats with foods rich in healthy fats. Cooking with oils is better than cooking with butter or lard. A quick lunch of a peanut butter sandwich instead of a slice of pizza will do your heart some good. Trading out some of the cheese on your sandwich for a slice or two of avocado is another smart move. If your calories are in excess, switch from whole milk or 2% reduced-fat milk to 1% low-fat milk or nonfat milk to trim both calories and saturated fats.

Trans Fats

Food manufacturers create both saturated and trans fats when they harden oil in a process called hydrogenation, usually to increase the shelf life of processed foods like crackers, chips and cookies. Partial hydrogenation converts some, but not all, unsaturated fatty acids to saturated ones. Others remain unsaturated but are changed in chemical structure. These are the health-damaging trans fats.

Many experts consider trans fats even worse than saturated fats because, like saturated fats, they contribute to insulin resistance14 and raise LDL cholesterol, but there's more bad news. They also lower HDL cholesterol (the good cholesterol).15 The American Heart Association recommends that we keep our trans fatty acid intake to less than 1% of total calories (less than 2 grams if consuming 1600 calories daily). Achieving this might be trickier than you realize because many foods touting No Trans Fats on their labels actually contain traces of these artery-scarring fats. That's because the law allows manufacturers' to claim zero trans fats as long as a single serving contains no more than 0.49 grams. If you eat a few servings of foods with smidgens of trans fat like margarine crackers and baked goods, you can easily exceed the recommended limit.

Identify traces of trans fats by reading the ingredients lists on food labels. Partially hydrogenated oil is code for trans fat. You know that there are at least traces of trans fat present. When oil is fully hydrogenated (the label will say hydrogenated or fully hydrogenated), it will not contain trans fats. Instead, the unsaturated fatty acids have been converted to saturated fatty acids.

Unsaturated Fats

As discussed, unsaturated fatty acids improve blood cholesterol levels and insulin sensitivity when they replace saturated and trans fats. There are two classes of unsaturated fatty acids: monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats.

Monounsaturated fat sources include avocados, nuts, seeds and olives. Peanut, canola and olive oils are additional sources.

There are several types of polyunsaturated fats, and they each have different roles in the body.

- Omega-3 fatty acids have been in the spotlight recently because of their role in heart disease prevention. ALA is an omega-3 fatty acid, and you can find it in walnuts, ground flaxseed, tofu and soybeans, as well as common cooking oils like canola, soybean and walnut oils. Remember that your body is unable to create ALA, so it's essential to get it in the diet. From ALA, your body makes two other critically important omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA), but the conversion is very inefficient. It's better to get EPA and DHA from fish. Not only are EPA and DHA important to the heart, but they also promote visual acuity and brain development in the fetus, infant and child; they seem to slow the rate of cognitive decline in the elderly; and they may decrease the symptoms associated with arthritis, ulcerative colitis and other inflammatory diseases. You will find them in bluefish, herring, lake trout, mackerel, salmon, sardines, and tuna.

- Omega-6 fatty acids are a second type of polyunsaturated fats. LA is an omega-6 fatty acid and has to be acquired through the diet. Sources of omega-6 fatty acids are sunflower seeds, Brazil nuts, pecans and pine nuts. Some cooking oils are good sources too, such as corn, sunflower, safflower and sesame oils.16

When you work on reducing whole-milk dairy, solid fats (like butter and bacon grease), and processed foods containing partially hydrogenated oils, be sure to replace them with unsaturated fats rather than simply adding extra calories to your usual diet. Otherwise you can expect to loosen your belt as you put on the pounds.

Don't fear fats. Instead choose them wisely, making sure you do not exceed your calorie needs. Enjoy foods with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats while limiting the saturated and trans fats.

Sources

Innerbody uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles. Read our editorial process to learn more about how we fact-check and keep our content accurate, reliable, and trustworthy.

The National Academies Press. Chapter 6: Dietary Carbohydrates: Sugars and Starches IN Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein and Amino Acids. https://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10490&page=265

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. U.S. Department of Agricultural, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010: pg 46

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. U.S. Department of Agricultural, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010: pg 29

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. U.S. Department of Agricultural, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010: pg15

Souza et. al. Effects of 4 weight-loss diets differing in fat, protein, and carbohydrate on fat mass, lean mass, visceral adipose tissue, and hepatic fat: results from the POUNDS LOST trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2012.

Anderson JW, Baird P et al. Health Benefits of Dietary Fiber. Nutrition Reviews. 2009 Apr;67(4):188-205

AICR report. WCRF/AICR's Continuous Update Project (CUP) https://www.aicr.org

Dunford M, editor. Sports Nutrition: A Practice Manual for Professionals, 4th Edition. American Dietetic Association, 2006.

Gaffney-Stromberg E, Insogna KL, et al. Increasing Dietary Protein Requirements in Elderly People for Optimal Muscle and Bone Health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 Jun;57(6):1073-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19460090/

Vegetarian Diets. Position of the American Dietetic Association. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109: 1266-1282.

Brown MJ, Ferruzzi MG, et al. Carotenoid bioavailability is higher from salads ingested with full-fat than with fat-reduced salad dressings as measured with electrochemical detection. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:396-403.

Riccardi G, Giacco R, Rivellese AA. Dietary fat, insulin sensitivity and the metabolic syndrome Clin Nutr. 2004 Aug;23(4):447-56. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15297079/

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. U.S. Department of Agricultural, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010: pg 26

Risérusa U, Willett WC and Hu FB. Dietary fats and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Prog Lipid Res. 2009 January ; 48(1): 44-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19032965/

Chardigny JM, Destaillats F, et al. Do trans fatty acids from industrially produced sources and from natural sources have the same effect on cardiovascular disease risk factors in healthy subjects? Results of the trans Fatty Acids Collaboration (TRANSFACT) studyAm J Clin Nutr March 2008 vol. 87 no. 3

Micronutrient Information Center. Linus Pauling Institute of Oregon State University. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/other-nutrients/essential-fatty-acids.